All I had to do then was figure out stories that would work for the bigger story I wanted to tell, and if I could just tell them as stories, then it was easy.

MIRANDA POPKEY TWITTER HOW TO

The structure of the book is in many ways how I got around it, because a thing I do know how to do is tell a story about what happened to me. Reading your books I have always felt a kind of suspense, and that, to me, is completely baffling. I think the biggest difference between the two of us as writers is that you are very good at plot. That you had to translate, you couldn’t just transcribe. I think the more interesting question is, what did the process of fictionalizing your own feelings feel like? How did you go about that? That’s something you and I have talked about a lot, that for both of us, learning to write fiction was the process of learning to take a real feeling and find the right fictional situation to put it in. Which, I understand why that is an interesting game to play - it is a game I have played in my own head! - but I don’t think it’s a fruitful question to ask in an interview. Mostly the people who have interviewed me have not been, thankfully, interested in trying to figure out how close the narrator is to me.

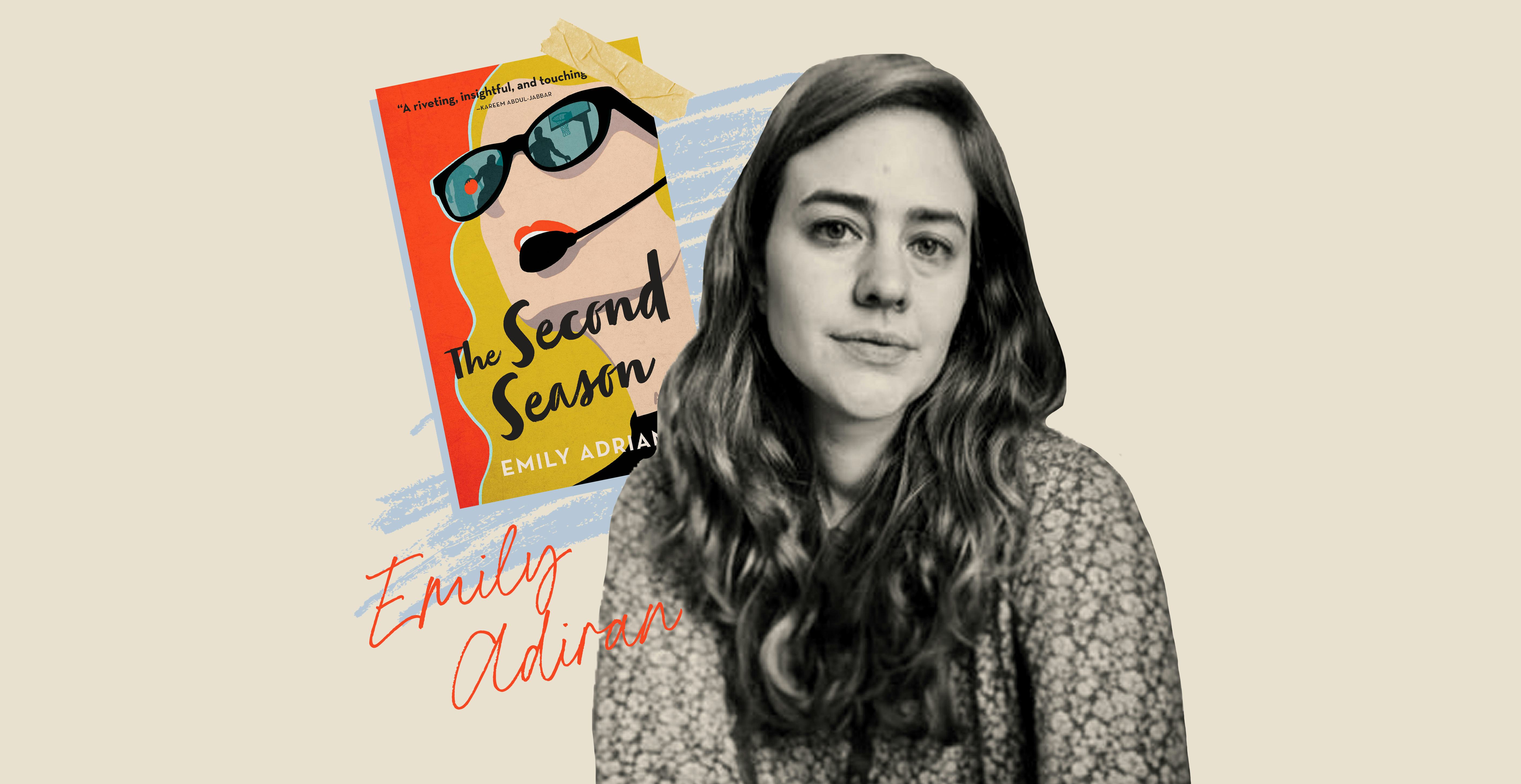

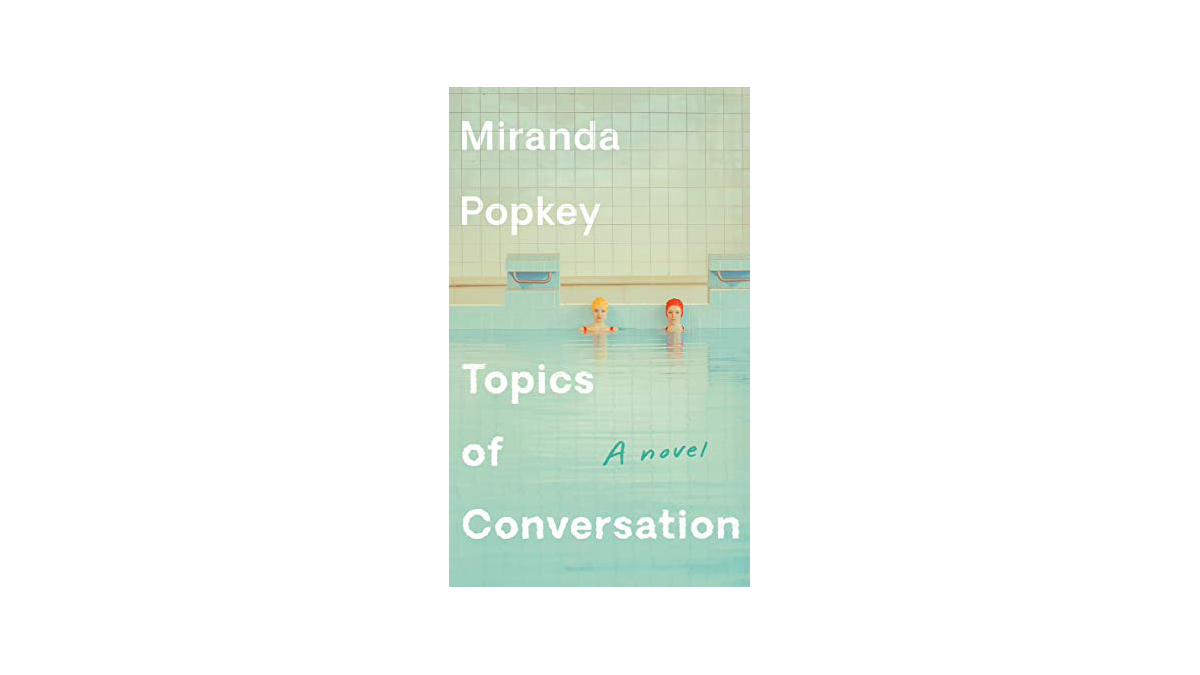

Which, in a way, is much more revealing, and grosser. But every feeling in the book is a feeling that I have had. I told the truth, which is that none of the things in the book happened, at least not in the way that they are described. The question was about how much coincidence there is between my life and the book’s narrative. That has not happened - mmmm, I think maybe that’s happened once. So when women write fiction, people’s response, often, is “Well, how autobiographical is this?” Has there been that, or have people been making the mistake of being like, “Tell me about your ex-husband,” and you have to be like… “No!” The interview has been edited for length and clarity. Miranda had done a different interview earlier in the day, which is why we start out discussing questions others have asked her. So of course I had to get her on the record for Longreads, to talk to her about how all of that talking - with me and with everyone else in her life - had finally led her to this book. (Ask her about it, she loves to tell this story, which begins with me being unable to work a hot water dispenser.) Over the course of the fifteen years we’ve known each other, we’ve talked endlessly about the topics her novel covers: about narrative and its pitfalls, desire and its darknesses, whether it’s possible to ever really be sure of what you feel, or think, or want. I’ve known Miranda since we were teenagers: we met in a dining hall our freshman year of college. (The stabbing is real the video, fictional.)īut she also, more and less incidentally, reveals herself as her own life unfolds in short story-like sections that cover the period from 2000 to 2017: her ambivalence about all of the stories she’s hearing, and the way that they shape her actions and her perception of her self.

Indeed, this nameless narrator spends much of the novel relating other people’s stories about their lives: repeating a conversation with a friend’s mother about an affair she had in her 20s, or describing a YouTube video of a woman recounting a party at which she almost witnessed the writer Norman Mailer stabbing his wife. “What I’m trying to say,” the narrator explains midway through Miranda Popkey’s debut novel, Topics of Conversation, “the theorem that must be accepted as a premise if any of my behavior is going to make sense, is that I have been, that I continue to be, best at being a vessel for the desire of others.”

Zan Romanoff | Longreads | February 2020 | 17 minutes (4,459 words)

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)